“The American West,” my brother once told me, “is like a Doors song. It’s vast and empty and mawkish and awe-inspiring.” The West’s huge open skies, towering mountains and sheer, jaw-dropping bigness are not only beautiful but an integral part of the American identity and the core of American mythmaking. So its no surprise that all the wonder and glory of the American West can make the eastern U.S. seem rather humble.

Such is the case in my home state of Massachusetts, a tiny state of modest geography and cramped, labyrinthine cities that would look not unlike a model maker’s exercise when places next to the sprawling cities of the Great Plains and the towering summits of the Rockies. Nevertheless, there’s plenty of natural beauty to observe in the woods of New England where a century of agricultural decline and urbanization have allowed the Northeast’s once clearcut forests to reclaim the fields and pastures that dominated the landscape. Here, great multitudes of cautious white-tailed deer and flocks of brazen turkeys are commonplace, as are porcupines, opossums, beavers and foxes. Coyotes, themselves transplants from the West, have moved to New England and ably replaced the gray wolves sadly driven out by farmers centuries ago; even black bears, moose, lynx and fishers prowl the woods. The chickadee, our state bird sings its songs from every treetop and in the summer the forest comes alive with the sounds of titmice, nuthatches, cardinals, goldfinches, bluejays and clever grackles, mourning doves and the ubiquitous dialect of the American Crow. The forests are full of life, tranquil and tremendously beautiful.

Photo by Cyndi Lavin – source: http://www.why-not-art.com/digital-pathways.html

It was these forests that inspired the transcendentalists, a group of writers and philosophers concerned with nature, spirituality and a dabbling of phrenology, some of whom you were likely forced to read in high school. The most famous is Thoreau, who spent his considerable leisure time traveling the wild and semi-wild places of early 19th century New England. The best known of these works is Walden, the account of his two years spent on Walden Pond in Concord, Massachusetts but more interesting to me (and hopefully you, considering its the subject of this post) is his 1843 essay, A Walk to Wachusett.

Mount Wachusett, where Thoreau walked to from Concord in 1842 is a mountain in central Massachusetts (lying on the border between Princeton and Westminster, MA) and the most prominent physical landmark near my home. Rising just over 2000 feet above sea level with a prominence of about 1000 feet, Wachusett is about 1/7th the height of Pike’s Peak in Colorado and about 1/5th its prominence; bluntly, it isn’t much of a mountain. Still, it is taller than any of the rolling hills that lie between it and the coastal marshland of Boston, 40 some miles to the east; in fact, it is the tallest mountain in the state to the east of the Connecticut river, being surmounted only by a few peaks in the far western Berkshire range (actually the southern end of Vermont’s Green Mountains) and Taconic range, most notably Mt. Greylock in the state’s far northwestern corner. Thoreau called Wachusett “the observatory of the state,” and the title is deserved: from its summit one can see New Hampshire’s Mt. Monadnock, distant Mt. Greylock, the skyscrapers of Boston (you know, the four of them) and the hills and towns of five states. Today Wachusett is best known for its ski area but its long been a tourist destination. Beginning in the 1870s, rail traffic from Boston and New York brought visitors looking to escape the city and enjoy the (relative) Arcadian bliss of Worcester county’s rural farms and woodlands. A hotel survived at the summit for nearly a century before burning down in 1970.

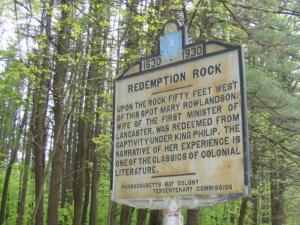

The name Wachusett comes from the Natick language of Massachusetts Indians; reports on its meaning are conflicted, but amount to something like “place near the mountain,” or “the great hill.” It was an important landmark for Native Americans and for the earliest European settlers; during King Philip’s War it would have loomed over the proceedings during the Redemption of captive Mary Rowlandson (an important landmark for colonial historiography which I won’t be able to resist covering in further detail in a later post;) indeed, it was long painted on the rear wall of my elementary school auditorium stage for a (no doubt thrilling) dramatization of just that story.

Today, Wachusett is still visited by throngs of people every summer. Like Walden, its status as a protected natural place and its proximity to Greater Boston give people who would otherwise not have access to natural places the opportunity to experience the quiet joy of New England summer in the heart of the woods. But historically, Wachusett had an outsized influence relative to its size, especially in the realm of seafaring.

Historically New England was the beating heart of the United States for fishing, whaling, shipbuilding and maritime trade. Codfishing and rum distillation from triangle trade Caribbean sugar where the most important industries for Colonial Massachusetts, whose indented coastline includes well protected deep-water harbors where ports such as Gloucester, Newburyport and New Bedford could thrive. New Bedford in particular would become the heart of the whaling industry; its from there that Melville’s ill-fated Pequod sails in Moby-Dick. Massachusetts was also a center for shipbuilding and in 1861 the USS Wachusett was launched from the Boston Navy Yard. It would go on to serve in one of the strangest theaters of the American Civil War.

The USS Wachusett was a Union sloop outfitted for war and it spent its first campaigns off the coast of Virginia, first participating in the blockade of the Southern states and then in several maritime battles and sieges. In late 1862 the ship would be made part of a task force assigned to hunt down Confederate “commerce raiders,” privateer warships largely built in British shipyards and sold to the Confederacy to sink and capture United States merchant ships and whalers. The USS Wachusett was tasked with capturing two commerce raiders operating in the Caribbean, the CSS Alabama and the CSS Florida. After two years of fruitless searching, the Wachusett tracked the Florida to Bahia, Brazil. The Confederate ship had taken shelter in Bahia harbor; neutral Brazil warned the two ships that if a confrontation were to occur the Brazilian Navy would retaliate against whoever fired the first shot. After several rounds of terse negotiations between the two American vessels, the Wachusett launched a night attack within the Brazilian harbor and captured the Florida and quickly escaped with its prize before the Brazilians could substantively retaliate. A diplomatic row between the Union and Brazilian governments ensued which ended in little more than the Wachusett‘s captain being temporarily removed from duty. Following the conclusion of the Civil War, the ship was sent to the China to hunt the infamous commerce raider CSS Shenandoah which was still operating in the Pacific. The two ships never met; the Shenandoah eventually surrendering in its de facto home port of Liverpool where, in a bizarre twist, it was sold to the Sultan of Zanzibar. The Wachusett would end its career guarding American economic interests in South America during the 1879-1883 War Of The Pacific between Chile, Peru and Bolivia.

The final maritime anecdote I’ll leave you with involves a curious object indeed: a nautical landmark which appears on maps printed to this day and that has never existed. This is “Wachusett Shoal,” named for the New Bedford Whaler that recorded its location in the south Pacific, thousands of miles from land in 1899. The captain recorded its location and wrote that it was a coral reef or shoal, 500 feet wide and 5 fathoms deep but no return voyage has ever found evidence that such an object exists. Wachusett Shoal is only one of several “phantom reefs” recorded in this area, including “Maria-Theresa reef,” “Jupiter reef,” and “Ernest Legouve reef.” There is no compelling evidence that any of them ever existed. One has to wonder what inspired this rash-this epidemic-of bogus reef discoveries. One thing for certain is that once something is put on a map you can expect every other map to keep it there too, even if its location was misplaced or debunked decades before, a cartographic habit which led to California being drawn as an island on maps for a century longer than contemporary navigational expertise would warrant. Thus, Wachusett Reef and its ilk still appear in this atlas published in the 1980s and internet reports suggest it appearing on maps as late as 2004.

As a final note, I’d be remiss if I didn’t try to tie this whole darn blog together and talk about comestibles. And so while Mount Wachusett has given its name to many local landmarks (and a few maritime oddities), it has, in the tradition of hinky craft brewers everywhere, given its name to a local beer. Wachusett Brewing, based out of Westminster, MA, makes several fine varieties of beer. They’re famous for their Blueberry Ale, though my favorites are the Green Monsta (a mild IPA or Bitter Pale Ale), the Summer Ale (a citrusy wheat beer) and the Octoberfest (a truly delightful red Marzen that blows local beer-king Sam Adams’s Octoberfest offering out of the water.)

If you’re ever in Massachusetts, go ahead and visit Mount Wachusett to enjoy the humble grandeur of New England’s forests and rolling hills. You won’t be disappointed.